A selection of the poems found and made during the workshop led by Abbi Flint.

Reflections on the moss poetry workshop from a natural scientist

Giles Johnson

As a scientist, I don’t use words as an art form. Writing is for communicating usually complex ideas in the simplest words possible. Short, simple, sentences. I did, unusually for a scientist, study English to A level, but that was a long time ago and the only poetry that is left is a few half-remembered lines from John Donne. If I ever knew how to write, I have long ago forgotten. I am not sure I even know what a poem is. The idea of an afternoon writing poetry in a room filled with artists, quite scared me.

When the time arrived, Abbi was quick to make this feel safe. The grandeur of the University Council Chamber is itself somewhat intimidating, but the group is friendly, and we were allowed to keep our work secret. The first exercise, free writing (is that what it was called?), encouraged us to spew words on paper without thinking. Triggered by a series of starter phrases, I took my mind to places I associate with moss, especially to the German forest I would be visiting the following week. Conifer plantations, generally bereft of diversity, are a rich place for mosses, being dark damp spaces where larger plants struggle to grow. The dim green light, the dampness, the sound of water mixed with birdsong, somehow landed on the page. My love of plants in general and forests in particular, goes back to the awkward geeky teenager, and led me to follow biology, rather than literature, when I went to university. So, writing about moss took me back to my youth as well as forward to my trip.

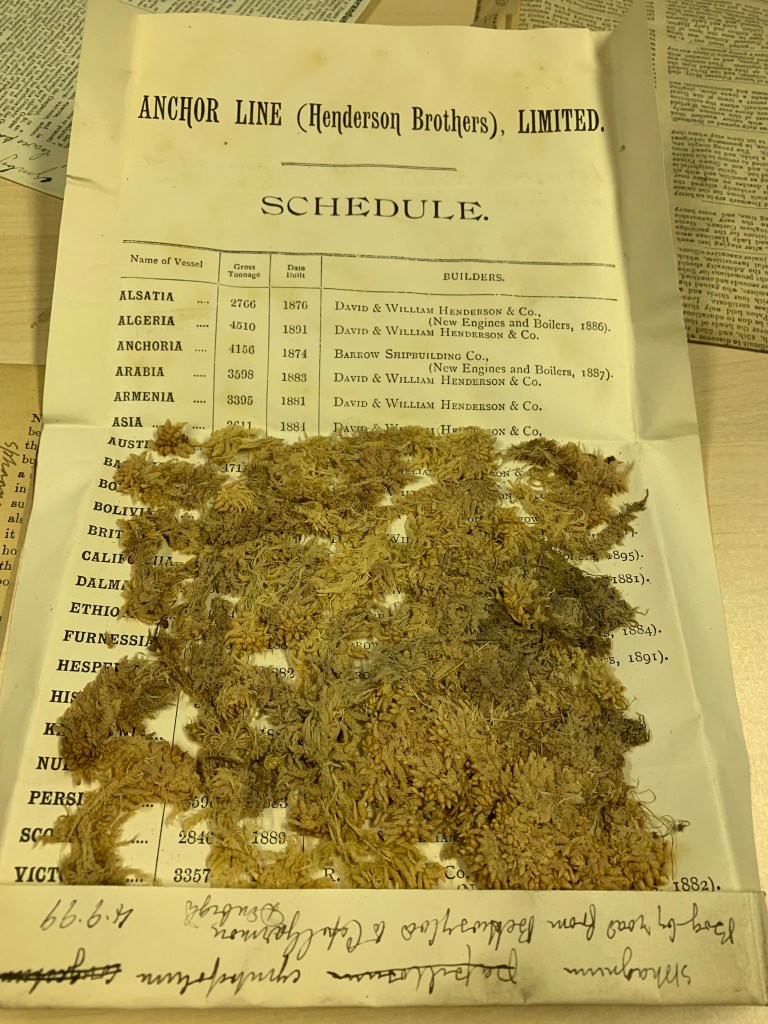

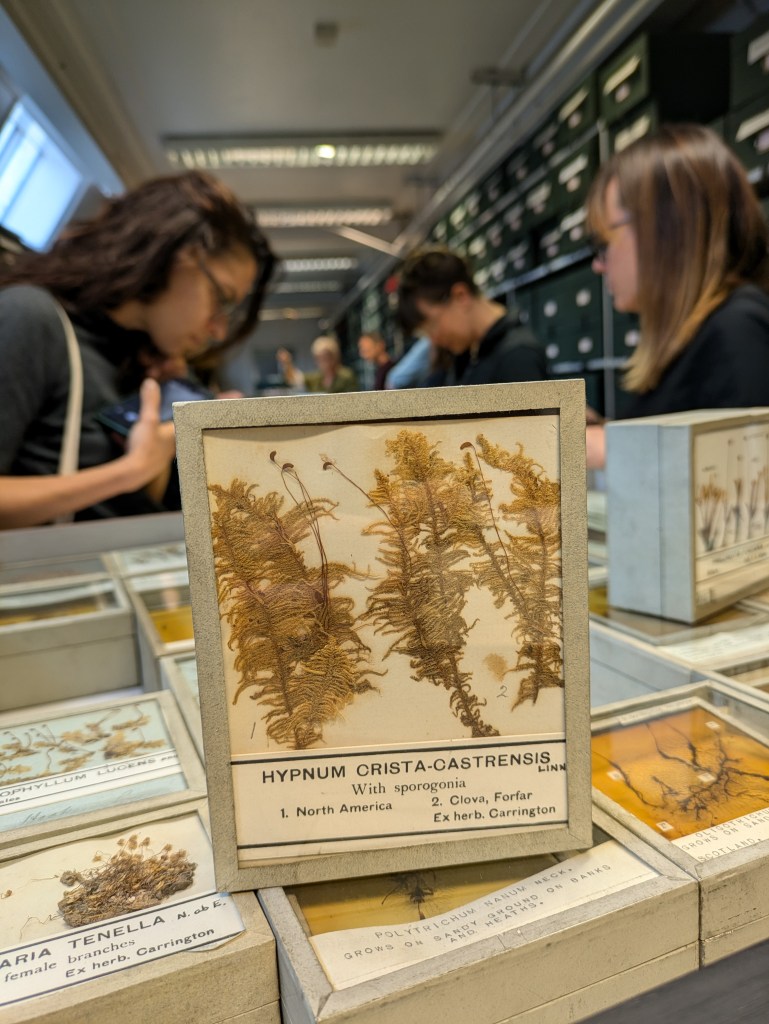

Unwrapping the moss packages that Abbi had prepared for the second exercise was an adventure, and the moss I was given was, to my surprise, one of the few that I can actually recognise without a guide. The poem I was inspired to write, if I am allowed to call it that, allowed me to focus my thoughts on the details of that small spikey plant, but again took me back to the forests where it grows.

My favourite activity was the construction of a “found” poem. The moss envelope itself was a copy of a letter from Richard Spruce, an eminent Victorian naturalist, to another, unnamed, colleague. The task – pick words or phrases from the text and use them to construct a poem. I felt less vulnerable doing this, in part because the words were not my own but also because the result just felt rather silly:

I keep pegging away,

I cannot do more.

I have been wishing for a long time

To pluck up courage,

Before the wintery fit,

To reflect that the battle

Against intolerance and superstition

Has to be refought in every age.

I have paid once this year

I cannot do more.

This also got me thinking about the sometimes poetic, more often silly scientific names we give to plants. So, also taken from the letter:

undulatum,

pulinatum,

schraderi,

minuta,

pusillus,

pearsonii,

woodii,

caespitosum,

inconstans.

The Uses of Moss

The old writers

delighted

in the many uses of moss:

Laplanders’ beds, small brooms (in northern England),

lights for Arctic nights.

Polytrichum cradles winter-weary bears,

Hypnum the squirrel, the dormouse, the bird.

Unnoticed, uncared for by passers-by,

moss harbours

what we little dreamed of:

elegant mollusca, tiny beetles, curious acari.

Adding their tribute to every mountain rill,

replenished by mist and snow-wreath,

myriad cells concoct an atmosphere –

both food and physic to the mind.

Anke Bernau, from R. Braithwaite, ‘The Moss World’ (1871)

Tortula Muralis

Tortula, Tortuga, tortoise.

Slow crawler, thin stick of fire.

/

Not content with being a sponge,

You are a pebble maker, stone breaker

Pinned with stems of bronze

/

Muralis, mural, mooring,

More than a flicker, you are a little mountain

Held close in the crack of a wall.

/

Red-grey rock hugger,

Stubbornly bristling upwards,

Without moving anywhere.

Henry McPherson

The l’s are often toothed

& the stips comparatively

Of all colours but blue.

The monoicous infl., the deeply bifid,

Separated with careful manipulation

Proved dioicous, sexuality left in doubt.

The London Cat of Brit Mosses

Served to beguile an anxious peril,

Making show of such minute plants.

She found it quite ripe.

Sophy King

from Richard Spruce

We were by the tumbling stream

We are by the tumbling stream,

by the rocks dripping with water,

developing our texture in the constant moisture.

We are on the ground, and we are among the stumps.

We may vanish to appear no more until succeeding sessions.

We are peeping over the wall.

We are in the bogs the clay soil, and on the old apple trees,

we are tenants of the neglected Flowerpot.

They are captivated by our verdant carpets.

They find us among the rocks of sandstone slate and limestone,

they find novelty in each district, whilst their search was in vain elsewhere.

They extended their lists, travelling yet further,

toward the commons so that they may find us.

They remove us with pocket knives and other necessary apparatus,

submitting us to the microscope.

reaping their richest harvests, they remove our surplus rocks and soil.

They squeeze out our water and lay us out and press us until quite dry,

reserved at their convenience, we are kept for years unchanged.

We developed our texture in the constant moisture,

by the tumbling stream and the rocks dripping with water.

Antony Hall, from Braithwaite, ‘Mosses’ (1883)

Tenanted by moss

A neglected flowerpot, the crevices

between bricks, the clay soil of stubble fields,

here these tiny tenants make their homes.

/

Tenacious, delicate of texture,

wet with winter waters and gone by spring

(but only waiting to come back).

/

On rocks dripping with water,

rocks of sandstone or slate,

limestone, mountain sides, old apple trees,

/

on commons, in lanes and woods, ground

and banks, in bogs

and on the stumps and trunks of trees:

/

here too we meet with moss:

Pottia, Ephemerum, Tortula Muralis.

And meeting with mosses like this

/

how do we greet them?

Ingrid Hanson, mostly from Richard Braithwaite, ‘Mosses’ in in Taylor, J. E. (ed), Notes on Collecting and Preserving Natural History Objects, London: W.H. Allen, pp. 145-158.

two poems by Rachel Webster:

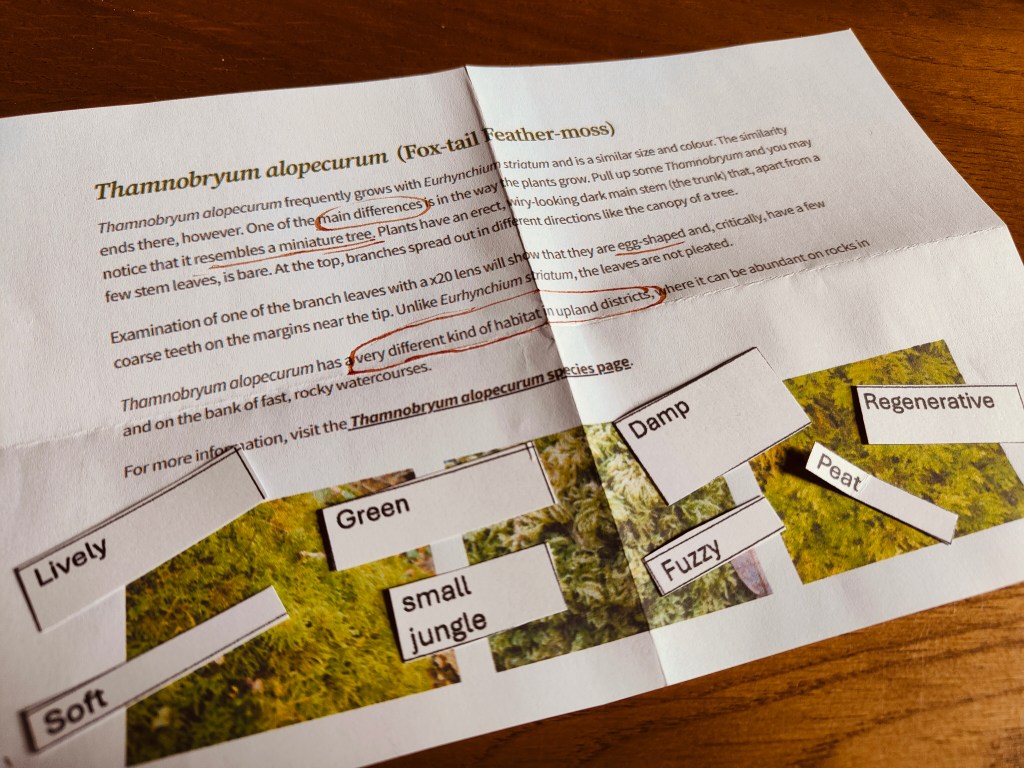

Fox-tail Feather-moss

(Thamnobryum alopecurum)

Trunks, reaching from below

Branches spreading to the light

Green, Lively

My small jungle of fuzzy trees

But why a fox?

Uplands, but not grounded in peat

Softly climbing the rocks

Water tumbling

My small jungle of fuzzy trees

But why a fox?

Feeling the damp in the leaves

Regenerative right to the tips

Toothed, egg-shaped

My small jungle of fuzzy trees

But why a fox?

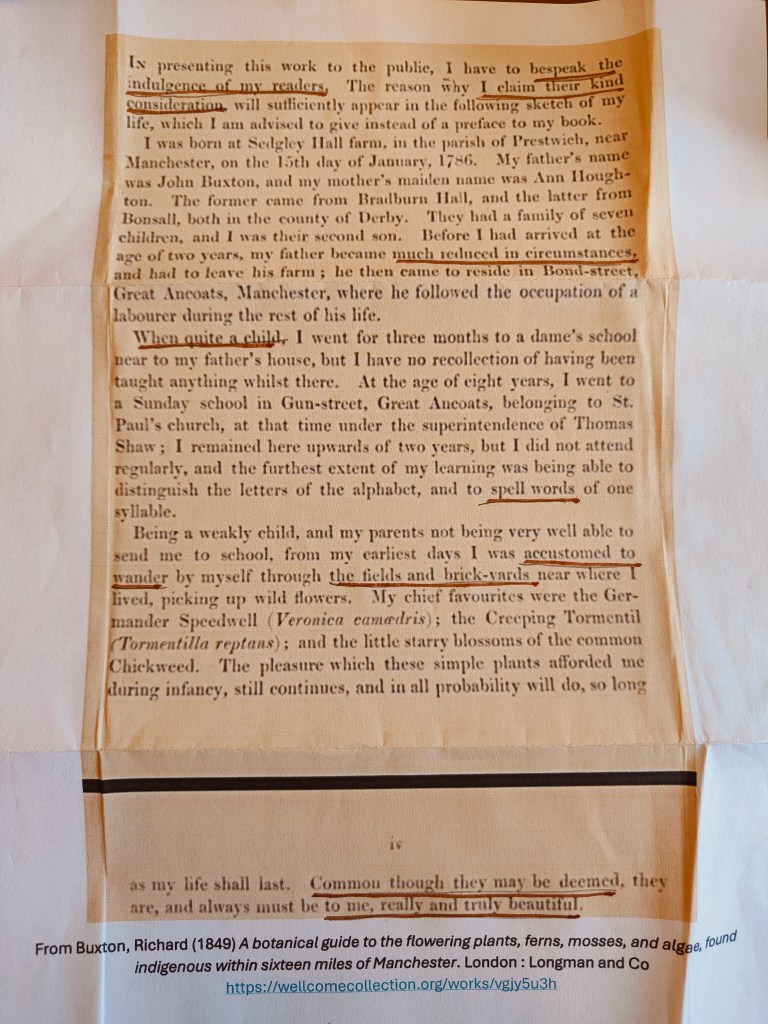

Preface to Richard Buxton’s “A botanical guide to the flowering plants, ferns, mosses and algae found indigenous within sixteen miles of Manchester.“

Much reduced in circumstances

When quite a child

the fields and brickyards

I was accustomed to wander

Common though they may be

to me, really and truly beautiful

common Chickweed

Germander Speedwell

Creeping Tormentil

starry blossoms

spell words

Winter brought mosses

Again dripping with water

with it they vanish

Aurora Fredriksen, adapted from Richard Braithwaite, ‘Mosses’ in in Taylor, J. E. (ed), Notes on Collecting and Preserving Natural History Objects, London: W.H. Allen, pp. 145-158.