Herbaria and Poetry as Research Method

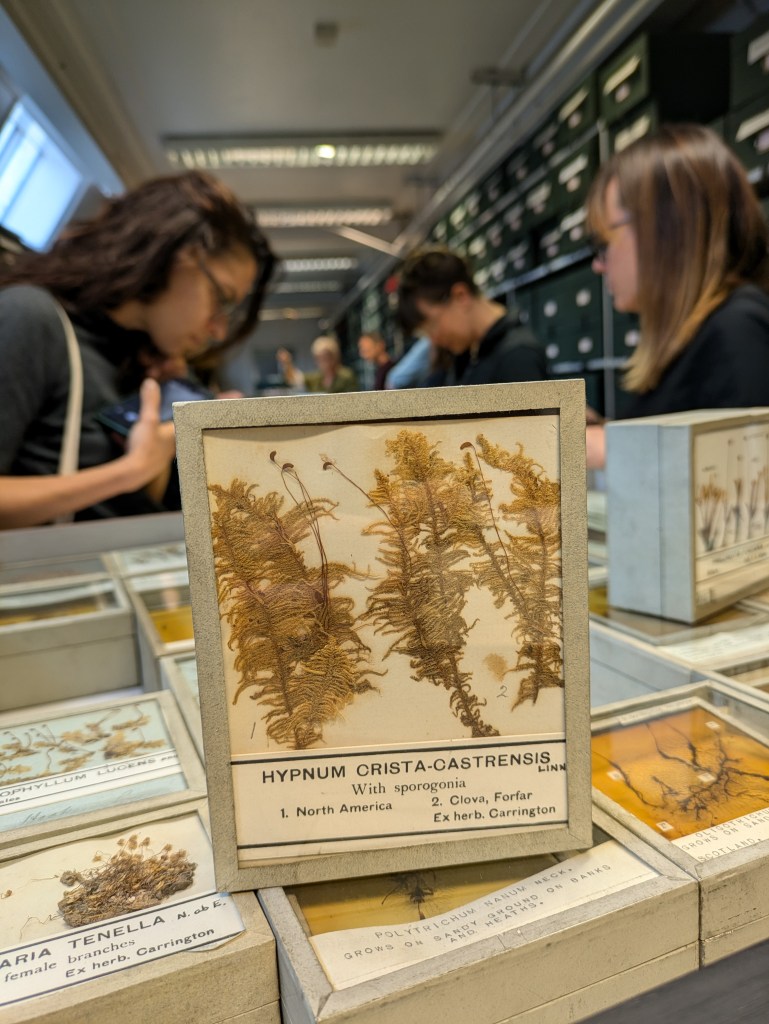

The morning session of this wonderful second workshop consisted of a tour of Manchester Museum’s Herbarium, under the expert guidance of Curator of Botany Dr Rachel Webster. Entering the herbarium imparted a feeling of childlike wonder, the promise of things waiting to be discovered. Drawers and drawers of the dried remains of mossworlds – ‘crispy and dry’, as Rachel said, rather than plump and verdant – lined narrow corridors. Here innumerable plants and plant parts are stored, after having been collected, preserved, filed and catalogued. The herbarium is also full of beautiful historical artefacts: Victorian cabinets and ornate boxes – or little wooden slides framing the minute remains of bryophytes suspended in amber resin. The plants, carefully pressed and dried, can look very different from how they would have appeared in life – and this is particularly true of mosses. Drained of colour, flattened and desiccated, they are separated from their worlds of relations, saved as individual specimens, taxonomised.

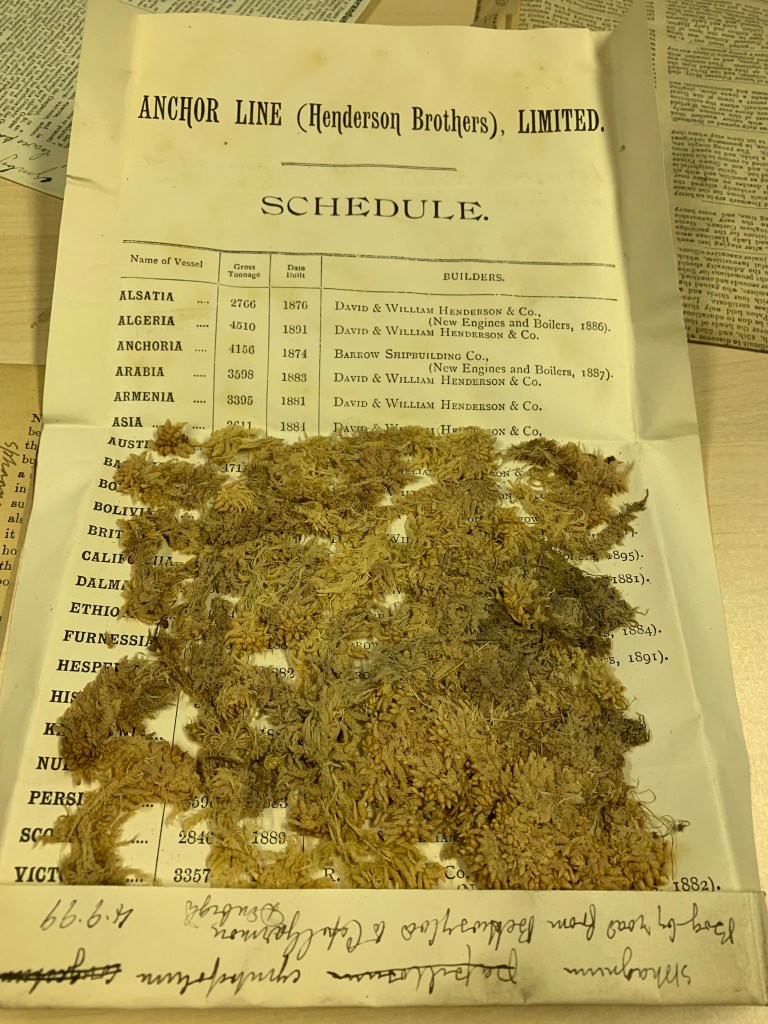

Many of the mosses have been collected in standard-construction envelopes (‘moss packets’), made of whatever paper the collector had to hand. The middle-class collectors in the nineteenth century were often employees of cotton-trading companies, shipping companies or other businesses and these occupations and their ephemera are reflected in what Rachel called an ‘accidental archive’. Such objects tell their own stories, alongside and entangled with the stories of moss. A sample of sphagnum cymbifolium collected at Coombs Moss on 6 June 1901 is folded up in a piece of paper printed with advice for those wishing to speculate safely (to whom some ‘carefully compiled guides’ can be sent, gratis!); another is tucked in an envelope whose yellowed outer side sports a single large advertisement for ‘How to Make a Good Income with Small Capital.’ It promises that ‘You will profit by reading’ its contents. This accidental archive, with its glimpsed stories and material clues, is a suggestive and intimate companion of the ‘official’ botanical archive. Yet the latter, too, holds stories that are only partially known – with much that has been hidden by the archival framing itself, and the politics and practicalities of botanical collecting.

Despite the sheer variety and wealth of material Rachel had selected for us, we were left with the realisation that we had seen only a tiny fraction of the herbarium’s extensive moss-related collections. All of these things – the herbarium as a space, the specimens it contains as well as their related material cultures – can tell us a lot about previous generations’ ways of knowing moss: what they thought was important, how they sought to preserve that knowledge, what they valued and why. The aesthetic pleasure we found in the archive was mingled with our awareness of the complex histories of collecting; the ethical and political dimensions of botanical knowledge production. The visit was lively, stimulating and fun – but it also invited us to reflect on the histories, assumptions and habits that shape our own practices; it made us think carefully about the contexts in which we do our work, and its ethical implications.

The museum specimens are full of stories waiting to be (re)told, of the plants themselves, but also of time and place. The second session of the day – a poetry workshop led by archaeologist-poet-researcher Dr Abbi Flint – ‘rhymed’ with the herbarium tour as it invited us to engage with the accidental and official archive, with playful seriousness. Poetry can feel very daunting to many of us, and we knew that this session would coax us into unfamiliar territory. Since the willingness to try the new, even to feel vulnerable, is for us very much at the heart of interdisciplinary collaboration, we hoped that everyone would feel able and willing to be open to what the session proposed.

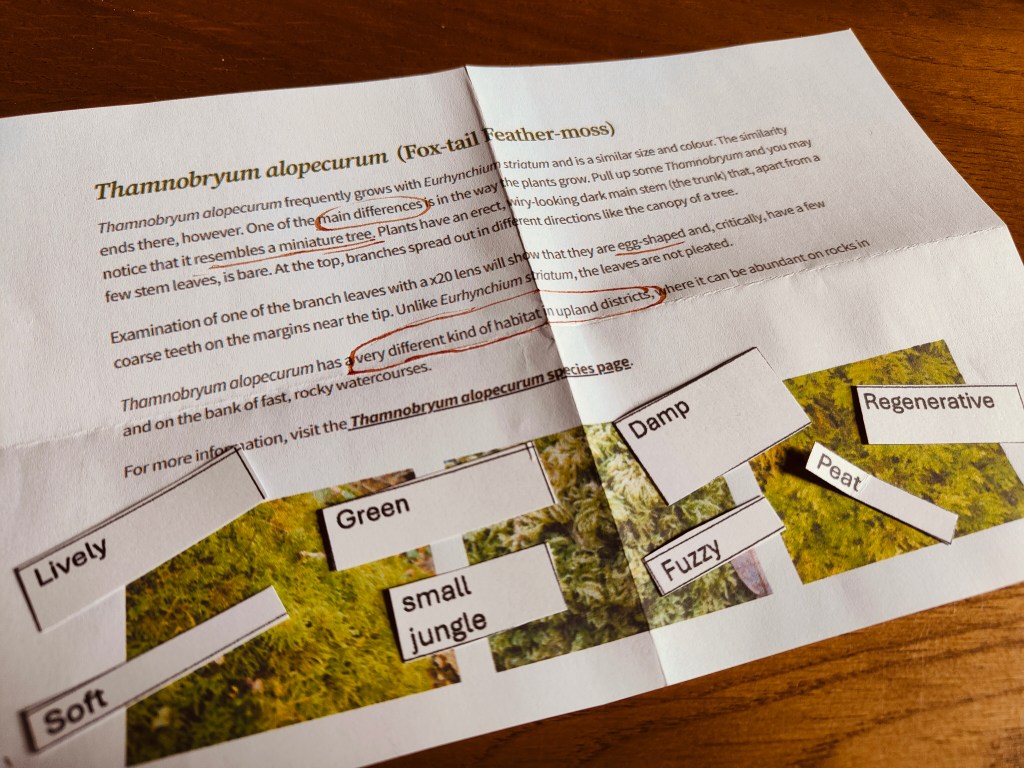

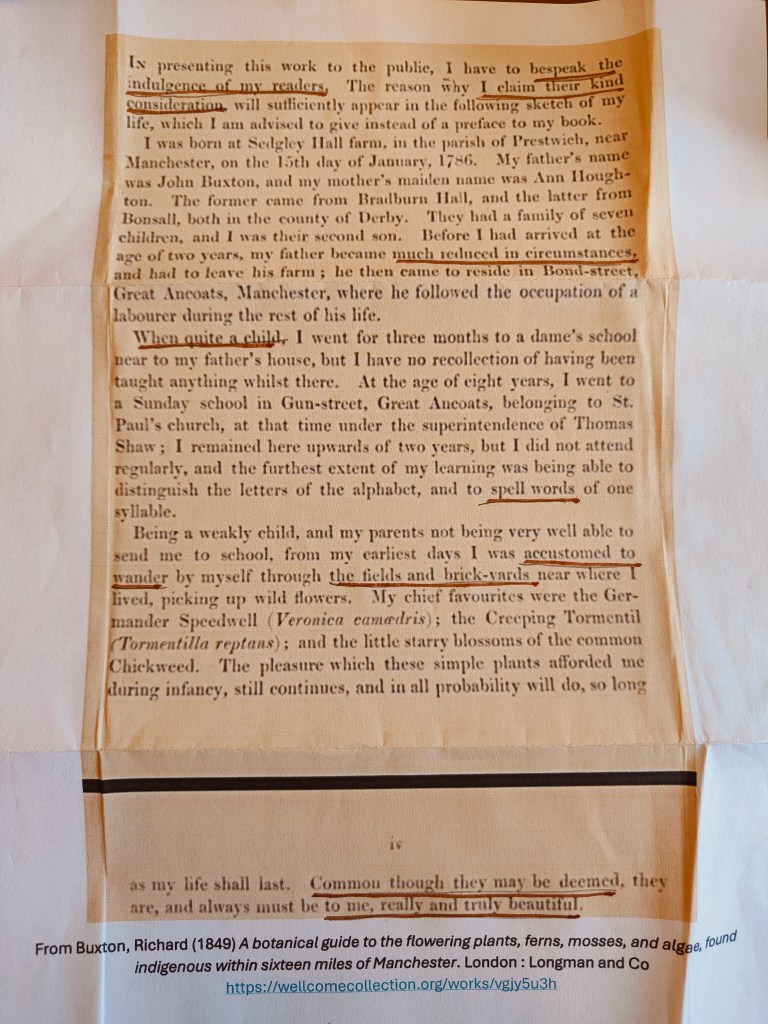

After fortifying ourselves with coffee and cake, we entered the grand surroundings of the Council Chamber, located in the Whitworth Building designed by the famous Alfred Waterhouse at the end of the nineteenth century. The space could easily have been intimidating, but we chose it because it – like the herbarium – offers a powerful reminder of the history, wealth and clout of such an institution. Abbi spoke to us about poetry as a research method and opened the session with a ‘free writing’ exercise, in which we responded to prompts that asked us to re-collect sensory details of moss (what it looks, feels, sounds like). This loosened up our writing muscles, as well as returning us to embodied encounters with mosses in diverse places such as urban streets, suburban gardens, upland peat bogs or damp riverbanks. A second exercise involved beautifully-crafted ‘moss packets’ that Abbi had made with paper featuring extracts from nineteenth-century bryological writings. Each envelope contained a picture of a particular moss, with its name and identifying features, and small pieces of paper bearing words commonly associated with moss (‘green’, ‘damp’, ‘soft’). Drawing on these, we wrote our own poems about ‘our’ moss. The final exercise was the ‘found poem’ – here we worked with the text extracts that were printed on the envelopes.

Crossing out parts of sentences until only the most striking phrases remained, we then created poems out of those words, new and old voices mingling. This was a perfect rejoinder to our herbarium visit, opening up an unexpected (and unexpectedly moving) way of engaging with historical materials: a way of escaping the structures and strictures of knowing moss that previous collectors had set, of looking anew at their worlds of moss – but also of seeing moss anew with the help of their words. The boundaries between ‘scientific’ writing and poetry, research and creativity, came to seem very porous, even if each also maintained its particularity. Abbi expertly created a safe as well as experimental space for us to think and write about mosses in new ways. The session allowed us to engage generatively with the writings of nineteenth-century bryologists, and to find our own (sometimes unsuspected!) voices in and through them. Do have a look at some of the reflections and poems generously shared by members of the team!

Aurora, Ingrid, Anke

Reflections from the session convenors

Rachel: After attending the brilliant first workshop with the combined efforts of Joey Pickard and Henry McPherson, it seemed clear that the best way forward for me would be to respond to the ideas they shared. This would also allow me to lean into one of the strengths of museum collections, helping people to have encounters with real and tangible things that can physically represent knowledge, theories or concepts. With an absolute wealth of ideas raised by the first workshop, it also felt very important to choose which ideas to follow with Abbi Flint so that we could give the afternoon some consistency.

Hopefully, the diversion into seaweeds, the beautiful moss model, and the boxed specimens were all helpful to recap some of the challenging bryophyte science and terminology from Joey’s foundational presentation. Books, labels, letters and handwriting represented the collectors, their histories and networks, and type specimens brought up discussions around naming. One thing that particularly spoke to me in workshop one was Joey’s use of scrap paper from a printer for moss-packet making. It was very reminiscent of the old moss packets in the museum’s collection, and I knew I wanted to show as many as possible in this workshop. I was delighted to find that Abbi was also excited to explore them. There is huge potential in the ‘accidental archive’ that develops in collections like a herbarium, where people have used all kinds of scrap papers to preserve their precious specimens.

Henry’s musical workshop was deeply rooted in our understandings of mosses, our encounters with them and emotion connections we may feel towards them. Collating our descriptive words revealed many similarities between us all, especially around notions of vitality, vivid colours and dampness. This is almost the exact opposite of describing the materiality of a herbarium collection. However, both bryologists (then and now) will be very familiar with dry moss collections. The way they identify mosses and understand their biology will have to encompass this duality of the characteristics between the living and the dried moss. I wanted to make sure that everyone had access to diverse material to explore this alternative moss world.

I have to admit I was approaching a poetry workshop with some trepidation, but Abbi skilfully introduced us to poetic inquiry and took us through several enjoyable writing exercises. I was surprised to find it quite easy to let the words flow when free writing, and the moss-packet contents were brilliant for helping overcome the blank page and get started (though I’m making no claims to quality!). What surprised me most was how challenging it was to repurpose the words of others into a poem. I have had years of training and experience working with the words of others, and it was so hard to step away from that; to prevent myself writing an abstract, or an extracted object label or abbreviated wall-text. I found myself looking to retain the original meaning or feeling and editing the text rather than using it as a source. More practise needed for this skill!

Abbi: In planning my contribution to this creative, interdisciplinary project, I was conscious that this was part of our ongoing collaborative conversations, opened so wonderfully by Joey and Henry in the first workshop. The different frameworks they provided had already prompted me to think about how I understand and relate to mosses in new ways. So many fascinating threads emerged from this workshop and it was difficult to decide where to focus for our poetic explorations, but there were a number of themes that I was particularly drawn to—the diversity of moss collectors and their practices, the different ways of naming of mosses and the meanings these evoke, and the embodied and sensorial nature of our encounters with mosses.

I was excited when Anke, Aurora, and Ingrid suggested that mine and Rachel’s contributions would be paired under the theme of ‘storying the archive’. Not least as I couldn’t wait to learn more about the collections in the museum’s herbarium and get to see behind the scenes of the museum! Rachel and I met in advance and she gave me a sneak preview into some of the materials she would be sharing, including texts and letters written by nineteenth century bryologists that I could draw on in the writing exercises.

Rachel’s tour of the herbarium was expertly curated and guided. I felt a sense of childlike wonder exploring the beauty and depth of the material she had selected. There was so much poetry here: the words of labels and archival texts, the physicality of the herbarium itself—its smells, sounds and textures—and the feelings and insights these evoked. One of the highlights for me was the ‘accidental’ (almost archaeological) archive of the moss packets themselves, which gave me the idea for the poetic moss packets I prepared for the workshop.

My workshop was very much an invitation for people to experiment with poetic approaches to thinking and writing with moss and archival materials, and I was thrilled that people seemed to accept this invitation and engage with the texts and their own writing practices in playful and thoughtful ways. We did not share our writing in the workshop, but some people generously shared their work with me after the session. I was struck by the different directions people had taken these in (even when working with the same texts) and the close attending that infused the poems, crafted with such care and insight. I hope to read more of this creative work as the project progresses.